Part 4: Machine Epsilon - The Smallest Change a Double Can See

23 Dec 2025

This post is part of my Floating Point Without Tears series on how Java numbers misbehave and how to live with them.

In my post on associativity and reduce1, we saw something that feels like a prank. In Example 5, adding 1.0 to 1e16 did not change the value at all.

double x = 1e16;

System.out.println(x + 1.0 == x); // trueThat is not Java being cheeky. That is IEEE-754 being literal. A double does not live on a continuous number line. It lives on a grid.

This post answers one question:

How fine is the grid?

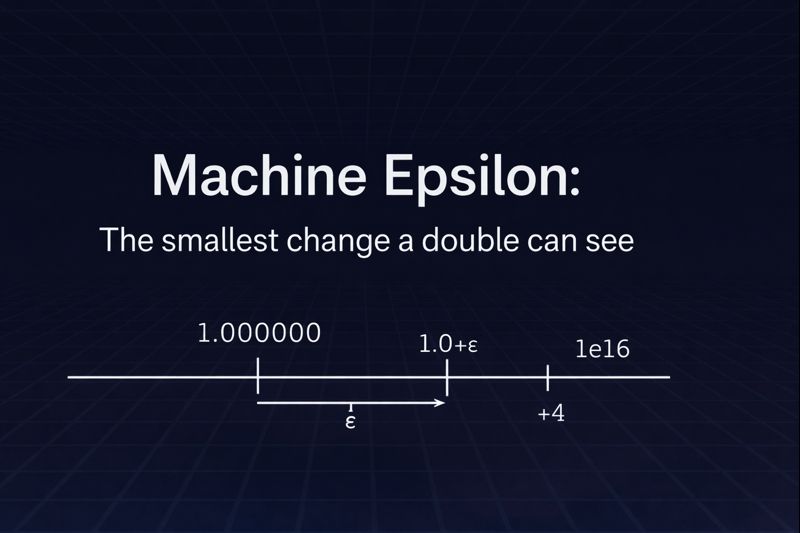

Machine epsilon and the first rung above 1.0

One common definition of machine epsilon (ε) is:

The smallest ε > 0 such that 1.0 + ε ≠ 1.0 for double.

This is “the gap from 1.0 to the next representable double above it”.

Note: Some references use ε to mean 2⁻⁵³, which is half this gap and represents the maximum relative rounding error for a correctly rounded operation. In this post, ε means the “next representable number above 1.0” definition, which is 2⁻⁵².

Finding ε in Java

Here is a loop that finds that smallest nudge.

public class MachineEpsilon {

public static void main(String[] args) {

double eps = 1.0;

while (1.0 + (eps / 2.0) != 1.0) {

eps /= 2.0;

}

System.out.println("epsilon = " + eps);

}

}Typical output on an IEEE-754 JVM:

epsilon = 2.220446049250313E-16That value is exactly 2⁻⁵². Since powers of two are exactly representable in binary floating point, there is no approximation error in storing this value. The decimal string 2.220446049250313E-16 is just how Java renders that exact binary value for display, rounded to about 15 decimal digits.2

One quick trap: Double.MIN_VALUE is not machine epsilon. Double.MIN_VALUE is the smallest positive double near zero (about 5×10⁻³²⁴). Machine epsilon is about spacing near 1.0.

The ladder model

Picture a ladder laid across the number line.

Near 1.0, the rungs are extremely close together. As the numbers get bigger, the rungs spread out.

Machine epsilon tells you the rung spacing near 1.0. But what you usually want is the spacing near whatever value you are actually using.

That spacing is called ULP, short for Unit in the Last Place.

Java gives it to you with Math.ulp(x).

How spacing grows with magnitude

Let’s sample the grid at a few scales.

public class UlpSpacing {

public static void main(String[] args) {

double[] xs = {1.0, 10.0, 1e8, 1e16};

for (double x : xs) {

System.out.printf("x=%-8s ulp(x)=%s%n", x, Math.ulp(x));

}

}

}Typical output:

x=1.0 ulp(x)=2.220446049250313E-16

x=10.0 ulp(x)=1.7763568394002505E-15

x=1.0E8 ulp(x)=1.4901161193847656E-8

x=1.0E16 ulp(x)=2.0That last line is the whole “Example 5” mystery solved:

Around 1e16, the grid spacing is 2.0.

So 1e16 + 1.0 lands between rungs and rounds back to 1e16. But 1e16 + 2.0 is exactly one rung up.

double big = 1e16;

System.out.println(big + 1.0 == big); // true

System.out.println(big + 2.0 == big); // falsePowers of two: where spacing jumps

ULP does not grow smoothly. It jumps at powers of two.

Right below 2ᵏ, spacing is one value. At 2ᵏ, spacing doubles.

That is why comparisons that seem symmetric can behave oddly if two values straddle a power-of-two boundary. If you’re comparing values near different powers of two, their ULPs can differ by a factor of 2.

Near zero: subnormals exist and they are weird

For very small magnitudes below Double.MIN_NORMAL (approximately 2.225×10⁻³⁰⁸), double switches to subnormal (also called denormal) representation.

What changes in subnormal land:

Normal doubles have an implicit leading 1. in the mantissa:

- value = (1.fraction) × 2^exponent

- This gives you full precision

Subnormals drop that leading 1.:

- value = (0.fraction) × 2^(minExponent)

- You lose precision gradually as you approach zero

Why they exist:

Without subnormals, there would be a hard cliff from tiny normal numbers straight to 0.0. Subnormals provide gradual underflow - a ramp instead of a cliff.

Key differences:

- Spacing becomes constant at approximately 5×10⁻³²⁴ (the value of

Double.MIN_VALUE) rather than scaling with magnitude - Arithmetic can be slower on some CPUs

- Relative precision is much worse (you may have only a few significant bits left)

Everything in the range (0, Double.MIN_NORMAL) is subnormal. That’s the range from about 4.9×10⁻³²⁴ up to about 2.225×10⁻³⁰⁸.

Most business code never goes near subnormals. Numerical code sometimes does. It is worth knowing that floating-point has an emergency mode near zero that trades precision for continuity.

Why tiny increments vanish when numbers get big

When your running total grows large enough, the local rung spacing can become bigger than the increments you are adding.

So “add a million tiny things to a huge sum” eventually turns into “add nothing, repeatedly,” because the tiny things fall between rungs and get rounded away.

That is not philosophical. It is mechanical.

Why equality checks on doubles are dicey

Sometimes two values that “should be different” land on the same rung. Sometimes two values that “should be equal” get rounded at different times and land on adjacent rungs.

So == is only safe when you mean exact equality:

- Comparing to exact literals:

0.0,1.0,-1.0 - Checking for special values: infinities, or

Double.isNaN(x) - Comparing sentinel values or results from identical deterministic operations

- Loop counters stored as doubles (though you should use integers instead)

When you need “close enough,” you need a rule that matches your domain.

A common practical pattern is absolute tolerance near zero plus relative tolerance for scale.

public final class DoubleCompare {

private DoubleCompare() {} // prevent instantiation

/**

* Check if two doubles are nearly equal using absolute and relative tolerance.

*

* @param a first value

* @param b second value

* @param absTol absolute tolerance (try 1e-9 for many applications)

* @param relTol relative tolerance (try 1e-9 for many applications)

* @return true if values are within tolerance

*/

public static boolean nearlyEqual(double a, double b, double absTol, double relTol) {

if (Double.isNaN(a) || Double.isNaN(b)) return false;

if (a == b) return true; // handles infinities and exact matches

double diff = Math.abs(a - b);

if (diff <= absTol) return true;

double maxAbs = Math.max(Math.abs(a), Math.abs(b));

return diff <= relTol * maxAbs;

}

}Choosing tolerance values:

absTolshould match the minimum meaningful difference in your domain. For scientific data measured to 3 decimal places, maybe1e-3. For pixel coordinates, maybe0.5.relTolis typically something like1e-9(about 9 decimal digits of agreement) for general use, or1e-6if you’re being more lenient.- These comparisons are slower than

==. If you’re comparing millions of values in performance-critical code, measure the cost.

This is not the only strategy, but it is harder to misuse than an “ULPs everywhere” helper.

Why parallel reductions can drift

Parallel reductions regroup operations. Floating-point addition is not associative, so regrouping changes when rounding happens.

Here is the smallest “this is why” example.

double a = 1e16;

double left = (a + 1.0) + 1.0; // first +1 vanishes, then second +1 vanishes

double right = a + (1.0 + 1.0); // (1.0 + 1.0) becomes 2.0, which moves one ULP

System.out.println(left == right); // false

System.out.println(left); // 1.0E16

System.out.println(right); // 1.0000000000000002E16Same values, different grouping, different result. That is the reason parallel sums can drift when the data has large magnitudes or mixed scales.

The takeaway

A double gives you roughly the same number of significant bits everywhere (about 15-16 decimal digits), not the same absolute resolution everywhere.3

Machine epsilon tells you the first rung above 1.0.

Math.ulp(x) tells you the rung spacing where you are standing.

And that is why, at 1e16, adding 1.0 is like whispering into a hurricane.

References

-

Part 2: Associativity, Identity, and Folding - Why Your reduce Keeps Biting You ↩

-

How is 2.220446049250313E-16 = 2⁻⁵²? 2⁻⁵² = 1 / 2⁵² = 1 / 4,503,599,627,370,496

1 ÷ 4,503,599,627,370,496 = 0.00000000000000022204460492503130808472633361816…

In scientific notation: 2.2204460492503130808… × 10⁻¹⁶

The displayed value 2.220446049250313E-16 is this value rounded to 15-16 significant decimal digits for display. ↩ -

For deeper reading, see David Goldberg’s classic paper, “What Every Computer Scientist Should Know About Floating-Point Arithmetic”.* ↩